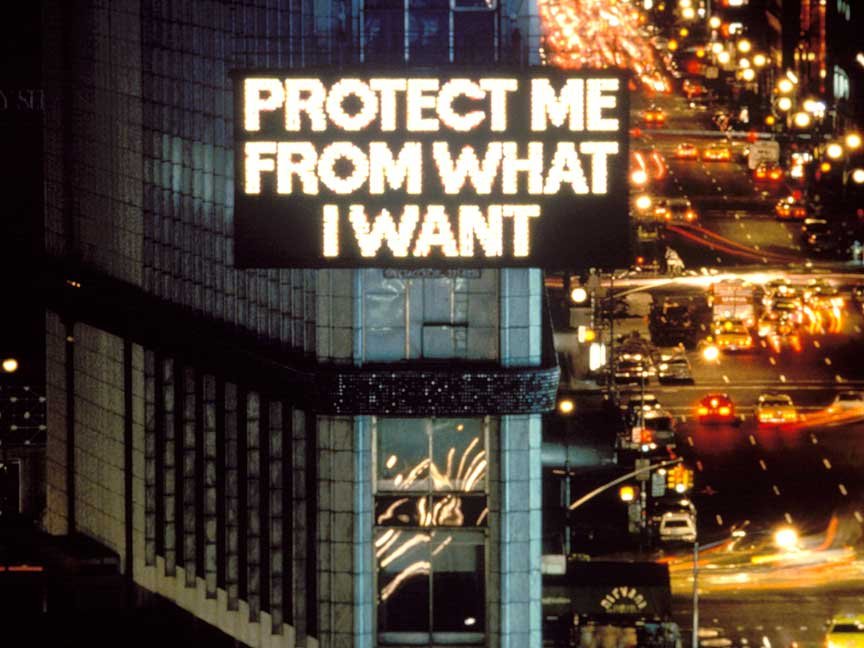

Shock art is a term that describes a style of art that meant to shock viewers through disturbing imagery, sounds, or scents. Considering our last project has a lot to do with interaction, I thought that this would be an interesting topic to blog about, especially given that shock art is so reliant on viewer involvement.

Some famous shock artists include Damien Hirst, Andres Serrano, and Piero Manzoni. All of these artists have infamous pieces that show the extremes of shock art. For example, Hirst created The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, a dead shark suspended in a tank of formaldehyde. Serrano created a piece called Piss Christ, a photo of a crucifix placed in the artist’s urine. Finally, Manzoni made a piece called Artist’s Shit in which he filled 90 tin cans of his feces. The piece was ultimately sold at Sotheby’s for 124,000 euros.

All three of these artists used shock as a way to spark conversation. Although many critics denounce this type of art as a cheap ploy, the style itself does raise the question of what should be constituted as art and why.

For more information on shock art and examples of pieces, click here.